What is hoarding disorder (HD)?

Hoarding disorder is new to the most recent edition of the clinician’s diagnostic manual (DSM-5), with hoarding previously categorized as a subtype of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Although individuals with OCD can engage in hoarding as a compulsion, most individuals with HD do not have OCD.

Hoarding disorder is associated with three key features:

-

Ongoing and significant difficulty getting rid of possessions (i.e., throwing away, recycling, selling, etc.), regardless of their value; and strong urges to save and/or acquire new, often non-essential, items, that if prevented leads to extreme distress. Non-essential includes items that are both useless (i.e., broken), as well as those with limited value (e.g., 10 skirts in every color but never worn)

-

Living space becomes severely compromised with extreme clutter, preventing one from using that space for its intended purpose.

-

Significant impairment in social, occupational, and other important areas of functioning as evidenced by:

-

Impaired physical health

-

Missed work and compromised employment

-

Financial problems

-

Housing instability including threat of, or actual, eviction

-

Social isolation

-

Emotional distress

-

Family stress

-

Two additional specifications include:

-

Whether the individual is also engaged in excessive acquisition (It is currently estimated that upwards of 80-90% of individuals with hoarding also experience excessive acquisition of items through collecting, buying, and even theft.), and,

-

Whether the individual has any insight or awareness that their behaviour is problematic.

Hoarding as a behaviour can exist in other mental health conditions such as schizophrenia, dementia and neurodegenerative disorders, genetic disorders, brain injury, autism spectrum disorder, and affective disorders. However, a comprehensive assessment of the function of the hoarding behaviour will assist in determining whether a diagnosis of HD is warranted, or whether the hoarding behaviour is part of another disorder. Once again, as this can involve some complex distinctions, we recommend assistance from a mental health professional.

Common features often present in hoarding disorder

-

Acquiring and/or having trouble discarding items that have little to no value (e.g., broken lamps, a new fondue set when you already own 2, stacks of expired coupons, etc.). This is distinct from a hobby such as stamp collecting and owning thousands of stamps, or an interest in car restoration and having a garage full of parts and equipment.

-

Commonly saved items include:

-

Newspapers

-

Magazines

-

Old clothing

-

Bags

-

Books

-

Mail

-

Paperwork

-

-

Items take on special significance such as an emotional connection, being part of one’s identity, or offering a sense of safety and security.

-

Clutter results from items being kept in unrelated groupings or piles, and in locations designed for other purposes. For example, important bills and paperwork are kept with expired advertisement mailings, on a pile in the bathtub.

-

Striving for perfection, including a sense of responsibility to fulfill the potential of an item or not to be wasteful.

-

Feeling good not bad. Individuals with hoarding report positive feelings when they acquire items, and/or relief from fear, sadness, grief, and other negative emotions, that would occur were they made to discard items.

-

Living space becomes severely hampered or impossible to use. For example, the oven or bath are filled with items preventing one from cooking or bathing, or a bedroom is filled to capacity so one cannot sleep in the bed.

-

Problems with thought processes are well documented, including:

-

Challenges in sustaining attention to important tasks

-

Disorganization, and difficulties sorting and categorizing items

-

Poor decision making- what to keep and what to remove

-

Too many ideas of how to re-use/fix a discarded item

-

Memory difficulties-use of visual cues to aid memory that goes awry

-

-

All of the above features contribute to significant functional impairment and /or emotional distress.

-

Less common features involve the hoarding of animals, hoarding in the elderly, and the role of theft in item acquisition.

Facts

-

Hoarding occurs in 2-6% of children and adults during their lifetime, with the average age of onset in late childhood and early adolescence

-

There are no gender differences

-

Hoarding runs in families

-

Onset is often preceded by a stressful or traumatic life event

-

In individuals with HD approximately 1/2 also have depressive disorder; 1/4 have generalized anxiety, social anxiety, or attention deficit/hyperactive disorder-inattentive type; and 1/5 have OCD

Typical thoughts and beliefs

-

"It might be important or useful someday"

-

"It makes me feel safe and secure"

-

"I must not be wasteful"

-

"Its my responsibility to ensure its used"

-

"I cannot make mistakes"

-

"I'm really attached to it. Its part of who I am."

Common situations or affected areas

-

Job absenteeism

-

Compromised physical and mental health

-

Living conditions

-

Organization and focus

-

Personal relationships

-

Personal hygiene

-

Financial strain

-

Social isolation

Ralph's story

Ralph is a retired English professor who has never married. He has lived in the same home for forty years, but has recently decided to move to Florida to be close to his sister. However, his first meeting with his realtor did not go well. Much to Ralph’s surprise the realtor seemed astonished at the amount of items in his home and expressed concern that he was not ready to sell. Ralph has since taken a closer look at his home and thinks she over-reacted. While he knows he is a bit of a "pack rat" he doesn’t see the problem. Yes, he cannot access his third bedroom properly as there are so many stacks of books and old journals in there, but this is his collection, and while he only uses half of his kitchen this is because he is not much of a cook, not because he is using the other half to store broken appliances with which he likes to tinker. After all, he only started storing them in that part of the kitchen because he wasn’t using it. And in all fairness, he has been in his home for forty years so of course all his drawers and surfaces are filled with stuff- surely this is the case in the homes of others? Ralph feels hurt and angry at the realtor’s words, but realizes he may have to part with some things to sell his home. However, this scares him as he has become quite attached to his things and feels overwhelmed at where to begin.

Self-help strategies

Step 1: Learning about stress and anxiety

No matter what type of anxiety problem you are struggling with, it is important to understand the facts about both stress and anxiety.

Fact 1: Stress is a normal and routine part of human life in the modern world. One definition of stress is any demand placed upon the body and mind. This "stress" may be both negative and positive. Therefore, dealing with your stress NEVER involves eliminating it but rather managing it.

Fact 2: Stress becomes a problem when we let life’s demands exceed the resources we have to cope. Resources can be both internal, such as our thoughts and feelings, and external, such as our actions, environment, and friends and family.

Fact 3: Anxiety is also a normal and adaptive system in the body that tells us when we are in danger. Therefore, just like stress, dealing with your anxiety NEVER involves eliminating it but rather managing it.

Fact 4: Anxiety becomes a problem when our body tells us that there is danger when there is no real danger.

-

As an important first step, you can help yourself a lot by understanding that the tension and pressure you may be feeling is stress, AND, that all of your worries, fears and physical feelings have a name: Anxiety.

-

Once you can identify and name the problem, you can begin dealing with it.

The next important step is recognizing how your anxiety problem is related to hoarding.

Step 2: Learning about hoarding

Hoarding disorder is associated with three key features:

-

Ongoing and significant difficulty getting rid of possessions (i.e., throwing away, recycling, selling, etc.), regardless of their value; and strong urges to save and/or acquire new, often non-essential, items, that if prevented leads to extreme distress.

-

Living space is severely cluttered, preventing it from being used for its intended purpose.

-

Significant impairment in social, occupational, and other important areas of functioning for the individuals including:

-

Impaired physical health

-

Missed work and compromised employment

-

Financial problems

-

Housing instability including threat of, or actual, eviction

-

Social isolation

-

Emotional distress

-

Family stress

-

Although hoarding disorder can create significant stress, impairment, and interference in the life of the individual, the good news is that there is a treatment that can help. Below we outline a variety of solution-focused, practical steps designed to help you (or your loved one), to sift through and organize possessions, so that you can learn to let go of unnecessary items cluttering your home (and life), as well as to challenge unhelpful ways of thinking that lead to urges to acquire and possess.

Step 3: Building your hoarding management toolbox

The best way to begin managing your Hoarding is to begin building a toolbox of strategies that will help you deal with your urges and behaviours over the long term. However, for most individuals who have been struggling with hoarding for years, we highly recommend finding a cognitive-behavioural professional with expertise in hoarding and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Our years of clinical experience dictate hoarding is a challenging disorder to address alone, and having a professional to guide you is advised. To access a list of qualified providers managed by the International OCD Foundation.

Tool 1: Become your own expert

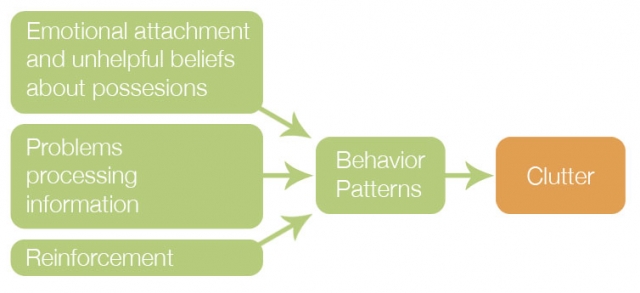

Understanding the factors contributing to your hoarding problem is a great place to start. This can help you identify what areas are most in need of change and what tools will work best. The following model identifies common reasons, that when combined, result in behaviour patterns that lead to hoarding and clutter.

-

Reason #1: Experiencing strong emotional attachment to possessions, and related beliefs about these possessions. For example, some adults believe that their identity is directly linked to their possessions, and thus were they to eliminate various possessions they would no longer be who they are. For others strong beliefs can lead to hoarding, such as beliefs about waste versus use, responsibility, sentimental attachment, and perfectionism and control.

-

Reason #2: Information Processing Difficulties. For example, many individuals with hoarding struggle to process information due to: challenges with attention and focus, difficulties with decision-making and categorization, and poor problem solving.

-

Reason #3: The power of reinforcement. Most adults with hoarding are aware of the power of emotions in contributing to their hoarding. It can feel exhilarating to bring a new item into the home, or relieving to sit among one’s possessions. But so too can one feel afraid, ashamed, guilty, and more, when one must get rid of an item. Seeking "good" feelings and avoiding "bad" feelings both reinforce hoarding actions.

-

The beliefs around possessions, the difficulty processing information and making decisions, as well as the positive emotions associated with acquiring and the anxiety associated with discarding, lead to behaviour patterns. If taken to a point that it begins to interfere, these patterns may be described as hoarding.

Tool #2: Get motivated

Not all individuals struggling with hoarding are motivated to tackle their problem. Motivation often needs to be cultivated. In reading this, you might be feeling ambivalent about making change, as for most of us, change can be a scary endeavor. However, you CAN become motivated.

-

Step 1: Identify your thoughts and beliefs that might be getting in the way of feeling motivated to make change. The following are some common examples, although this is not an exhaustive list:

-

"It might be important or useful someday."

-

"Its not that bad of a problem."

-

"I must not be wasteful."

-

"Its my responsibility to ensure its used."

-

"I cannot make mistakes."

-

"I’m really attached to it. Its part of who I am."

-

-

Step 2: Look at the reasons to change your behaviour. Take a sheet of paper and draw a line down the centre. On one side list all the reasons to change, and on the other list all the reasons not to change. It can also help to give each item an importance/value rating. Not changing because you don’t have sorting bins should not be weighted the same as, changing so you can have a better social life. Is one side weighted more heavily than the other? And if it is the not change side, can some of those items be easily solved so they can be removed (such as, "I don’t have sorting bins.")?

-

Step 3: Look to the future. It can help to map out what the future may look like for you should you choose to begin to make changes, or not. Develop the following lists:

-

I want to get rid of hoarding in my life because...

-

If I work on my hoarding problem, the following will happen...

-

If I don’t work on my hoarding problem, the following will happen...

-

My personal goals are… (Goals can range from small, e.g., I can sleep in my bed again, to big, e.g., I can entertain in my home). List as many specific goals as you want.

-

*For more information about goal setting, see Guide For Goal Setting.

Tool #3: Get organized

Becoming organized is best achieved by taking small, baby-steps, one day at a time. Breaking large goals into small individual steps will help you to reach your goals faster, rather than adopting a do-it-all-at-once approach. Consider some of these ideas to assist:

|

Do... |

Don't... |

|

Set specific, measurable goals. E.g., I’ll clean out one drawer. |

Set vague, hard to measure goals. E.g., I’ll clean the kitchen. |

|

Establish a small time to work, daily. E.g., 10 minutes, twice a day. |

Try to do too much at once. E.g., I’ll work every morning, this week. |

|

Eliminate distractions. E.g., Turn the ringer off, keep TV or radio volume low, if on, and focus only on the task before you. |

Multi-task. E.g., Watch a movie, cook a meal, take a call, all as you are sorting, etc. |

|

Be flexible. E.g., If you planned to clean out one room but you are finding it too overwhelming, set a smaller task. I’ll start with this pile first. |

Be rigid. E.g., I must clean this room otherwise I’m a failure. |

|

Determine the outcome. E.g., Each possession needs to have a dedicated outcome. Typical options are: Garbage; Recycle; Donate; Sell; and, Keep. |

Postpone the outcome. E.g., I’ll decide what I want to do with the “go” pile later. I’ll make two piles for now- Go and Keep. |

|

Categorize. E.g., Every item gets placed into a category, which in turn belongs in a specific location. These might include: Papers (desk draw), clothing (bedroom closet), souvenirs (living room shelf), toiletries (bathroom), etc. |

Generalize. E.g., Items are placed in generalized groupings that make minimal sense. E.g. Keeping items from a vacation, in a pile in the hallway. |

|

Be systematic. E.g., Use the OHIO principle. Only Handle It Once. As soon as you lay hands on the item, determine it’s outcome and place it in a category and location. |

Be chaotic. E.g., Handle items multiple times until you “feel” ready to determine it’s outcome and category. |

In order to support your organizational efforts, locate supports in your area. Many charities will pick up donations from the home. Some recycling centers will make curbside pickup for large items such as electronics. Online stores allow you to post items for sale (e.g., E-bay and Craigslist). And the Internet is a wealth of information about how to handle specific items and situations. For example, a simple search can yield advice on how to dispose of excess pharmaceuticals, what to do with unused cleaning supplies, and more.

Tool #4: Develop other important skills

Organization and sorting are critical components to making a dent in tackling your hoarding problem. However, your ability to organize and sort items will be maximized with the addition of some other important skills. These include:

Skill #1: Problem-solving. Individuals with hoarding often struggle to problem solve. Unfortunately, this is a much-needed skill to assist with organization. Problem solving can help you identify key problems, and generate effective solutions. For information on how to use problem-solving skills, see How to Solve Daily Life Problems.

Skill #2: Decision-making. Indecision is a common struggle for most adults with hoarding. This may be due to perfectionism and fear of failure, among other problematic beliefs, intolerance for uncertainty, as well as neurobiological factors that impede thought processes that are needed to make decisions in life. The following questions can assist in increasing comfort in making a decision to discard items, given this is most often the desired decision in sorting and organizing.

-

How many do I already have, and is this enough?

-

Do I have enough time to use, review, or read this item?

-

Have I used it in the past year?

-

Do I have a specific plan to use it within the near future?

-

Does the item fit with my values and goals?

-

How does it compare to the things I value highly?

-

Does this seem important just because I am looking at it now?

-

Is it current/up-to-date, or in good, useable shape?

-

Do I have enough space for it?

-

Do I really need it?

Skill # 3: Managing paper in my home. Many people are unaware of how long to keep paper receipts, contracts, documents, etc. Fortunately, there are well-established guidelines that can assist (However, these guidelines may differ from country to country).

-

Keep for a month

-

Credit-card receipts

-

Sales receipts for minor purchases

-

Bank deposit slips

-

-

Keep for a year

-

Paycheck stubs/direct deposit slips

-

Monthly statements from bank, credit card, brokerage, retirement, etc.

-

-

Keep for seven years

-

Government materials for tax returns

-

Year end credit card and banking statement summaries

-

-

Keep for indefinitely

-

Tax returns

-

Receipts for major purchases of importance

-

Real estate and residence records

-

Wills and trusts

-

-

Keep in a Safe-Deposit box

-

Birth and death certificates

-

Marriage Licenses

-

Insurance policies

-

Automobile titles

-

Property deeds

-

Passports

-

It can be a huge help to opt for online record delivery rather than paper mailings. This prevents having to deal with extra papers coming into the home. Many stores are also starting to shift to offering email receipts. This is advised.

Tool #5: Assessing and modifying my thinking

Adults with Hoarding, like those with other anxiety disorders, tend to fall into thinking traps, which are unhelpful and negative ways of looking at things. These traps are a contributing factor to accepting new items or avoiding discarding items, or procrastinating on making decisions about how to manage an item. Over time, these thoughts trap you into ongoing hoarding. Use the Thinking Traps Form to help you identify the traps into which you might have fallen, and use the Challenging Negative Thinking handout to help you with more realistic thinking (For more information, see Realistic Thinking).

Tool #6: Making behavioural change: AKA clearing out!

Once you have worked through tools 1-5, you are likely ready for the final, and perhaps most important tool, clearing out! There are two methods to support making behavioural change towards clearing out your clutter. The first involves establishing a hierarchy, or list, of easiest items to discard, to hardest items to discard, and gradually moving up your hierarchy or list, item by item. The second method can be used alone, or in tandem with the first method. This method involves developing a behavioural experiment, to test out beliefs that might be preventing you from discarding an item for fear of the consequences, even though feared consequences are not guaranteed. These methods are outlined here.

Method #1 - Exposure: Discarding and non-acquisition practice:

Begin by creating a list of the items you want to discard but are having trouble doing. We advise creating multiple lists, for example, by room or by category. This will allow you to focus on one area at a time and reduce feeling overwhelmed or giving up. Once you have your lists, pick a first list and rank order each item from 0-10. Assign a 0 for the item that is the least scary or difficult to discard, to 10 for the item that is the most scary or difficult to discard. For example, if you have developed a toiletries list, wrappers may be a 1/10 on your ladder, whereas a hand held mirror from your aunt may be an 8/10 or 9/10. See Examples of Fear Ladders for some ideas about building your fear ladder.

Climbing the fear ladder. Once you have built a fear ladder, you are ready to face your fears by putting yourself in situations that bring on your fear or discomfort (exposure). In this example, you are exposing yourself to the act of discarding your items. Feeling anxious when you try these exercises is a sign that you are on the right track.

-

Bottom up. Start with the easiest item on the fear ladder first (i.e., fear=2/10) and work your way up.

-

Track progress. Track your anxiety level throughout the exposure exercise in order to see the gradual decline in your fear or discomfort of a particular situation. Use the Facing Fears Form to help you do this.

-

Don't avoid. During exposure, try not to engage in subtle avoidance (e.g., thinking about other things, talking to someone, planning to get an item back or to replace it.). Avoidance actually makes it harder to get over your fears in the long term.

-

Don't rush. It's important to try to do one item at a time and not take on too many to feel overwhelmed. People can sometimes feel a sense of relief once the item is gone—the anxiety peaks during the discarding process and can decrease quite quickly once the item is gone.

TIP: Regardless of its intensity, a fear will peak and then level off. If you do nothing about it, the fear will eventually go away on its own.

How to move on. Once you experience mild anxiety or discomfort when getting rid of items on a specific step of the ladder (e.g., 4/10), you can move on to the next step (e.g., 5/10). For example, after discarding all the empty shampoo and related containers from the bathroom (2/10), you might feel very little anxiety and feel calm. You can then challenge yourself to tackle the rest of the bottles that contain small amounts of product, but aren’t being used (3/10). Again, engage in this practice until your anxiety drops and the process seems easier or more manageable. This is a good guide to know when to go to the next step on the ladder.

Exposure for non-acquisition practice: You also can develop a hierarchy, and engage in exposure, for non-acquisition of items in addition to discarding items. In this scenario you will engage in the same steps outlined above, except the items on your list will not be items to discard, but items/situations to expose yourself to, with a plan NOT to obtain them. For example, it may be relatively easy to drive past an expensive store and not go in and buy something (2/10), medium hard or uncomfortable to go to a book drive and not purchase or acquire (5/10), and most hard/uncomfortable to decline a gift from a friend (9/10).

*For more information on how to do exposure, see Facing your Fears: Exposure.

Method #2 - Behavioural experiments:

This method involves creating an experiment to test out beliefs about discarding or non-acquisition. Many individuals with hoarding have developed beliefs that are inconsistent with their values. For example, "my stuff is what makes me happy," yet valuing social engagement with others, which is prevented due to excessive clutter in the home. Following this example, an experiment might involve having the individual gradually remove clutter from the back porch, and then inviting a friend over for a backyard BBQ. Predictions about what might happen would be made, as well as discomfort ratings generated for discarding the bikes.

The following questions can help design your experiment:

-

My experiment (What I will do): Discard broken bikes from back porch.

-

What I predict will happen (What I am afraid of?): Porch will feel naked and I will miss the bikes. Sadness will make it impossible to enjoy the space.

-

How strongly do I believe this will happen (0-100%): 75%

-

My initial discomfort (0-100): 85%

-

What actually happened? After a few hours my # dropped to 40%. After a few days I started to use the space to have coffee in the morning. I had a friend over for a BBQ and that felt really good.

-

My final discomfort (0-100): 5%.

-

Did my prediction come true? Not really. I still occasionally miss the bikes, but the space is totally worth it and I love entertaining.

Step 4: Continuing your successes

A word about success: Learning to manage your HD takes a lot of hard work. If you are noticing improvements, take some time to give yourself credit: reward yourself! However, success is sometimes hard to see. This can be true especially when you have many items to clear, but this does not mean you are not working hard. Be kind to yourself even when you have made what may seem a tiny step toward your end goal. Remember each "tiny" step will still get you where you want to go!

How do you maintain all the progress you’ve made? Practice! Practice! Practice! The Hoarding management skills presented here are designed to teach you new and more effective ways of dealing with your Hoarding urges and behaviours. If you practice these skills often, you will find that your symptoms will have a weaker and weaker hold over you. Learning to manage anxiety, stress, and Hoarding symptoms is a lot like exercise—you need to "keep in shape" and practice your skills regularly. Make them a habit, even after you are feeling better and you have reached your goals.

For more information on how to maintain your progress and how to cope with relapses in symptoms, see How to Prevent a Relapse.

About the author

Anxiety Canada promotes awareness of anxiety disorders and increases access to proven resources. Visit www.anxietycanada.com.