The building blocks of self-compassion

Reprinted from the Nourishing and Moving Our Bodies issue of Visions Journal, 2023, 19 (1), pp. 10-12

It takes a special type of energy to be kind to ourselves during hard times. One name for that energy is “self-compassion.” Self-compassion is defined as being aware of our experiences in times of difficulty and motivated to relate to ourselves with kindness and understanding.1 Research has shown that self-compassion is widely associated with resilience and good health.2

Unfortunately, many people find it difficult to be self-compassionate, and this is especially true for individuals who have eating disorders. This presents many challenges, as barriers to self-compassion are associated with less benefit from eating disorder treatment.3

What can clinicians and family members do to support vulnerable individuals to overcome barriers to self-compassion? In order to answer this question, our research team asked individuals working on recovery and graduates of the St. Paul’s Hospital Eating Disorders Program to share their experiences.

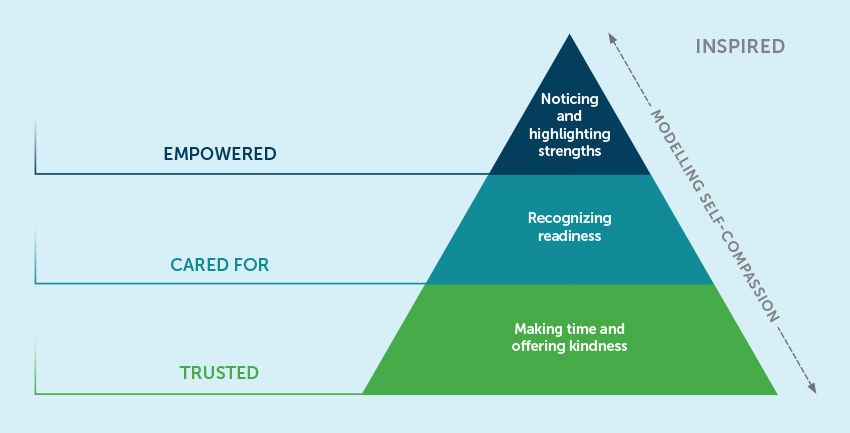

Interestingly, the most prominent theme that emerged was patients’ desire for validation. One definition of validation is the process of understanding, acknowledging and accepting another person’s feelings.4 Our team did a deep dive to learn what exactly validation means to our patients and what behaviours from family members and clinicians can help.5 Patients’ responses led to the creation of a model for loved ones and care providers (see figure below).

Making time and offering kindness

Shame may play a role in patients avoiding or concealing their needs. As a result, it is common for them to not feel seen. Patients in our study said that being invited to talk about what they were going through and having carers actively listen, show curiosity about their experiences and be fully present set the stage for a deeper connection with them.

This type of support provided needed respite from habitual self-criticism and blame, and planted seeds of acceptance for the challenges they were facing. These experiences helped patients view themselves in a kinder manner. Having time, space and a compassionate perspective created feelings of trust.

Here are some comments from patients:

“The feeling is relief, you feel you can be yourself almost… no fear of judgment from others”

“It’s compassion and acceptance…makes it so safe to tell her more…suddenly it’s not as shameful anymore.”

Recognizing readiness

Often, patients feel frustrated by care providers recommending treatment that they do not feel ready for. In our study, some patients who felt unworthy of care described how care providers’ acknowledgement of their illness severity helped counteract these feelings and gave them hope that recovery was possible. In other cases, patients who did not feel ready for treatment found it helpful when care providers supported them to step away from programming that was not suited to their needs. When care providers advocated for patients’ access to treatment that matched their physical and emotional needs, they felt cared for. Patients said:

“Once I saw the [referral] letter, there was a lot of validation with that and all of a sudden this became a real thing…this is the first thing that said the medical community says I have a legitimate sickness...”

“I wasn’t made to feel like I was letting anybody down if I were to choose not to go further. And I think that was really important because that actually helped me to decide to go further...”

Noticing and highlighting strengths

Patients said that when their symptoms began to improve, care providers often assumed they no longer needed support. In fact, this is when they said they needed support more than ever. Patients in our study emphasized that change is hard and that it was helpful for their hard work and struggles to be acknowledged along the way. When care providers recognized their strengths, expressed faith in their ability to make changes and reframed setbacks as a normal part of recovery, they felt empowered. One patient spoke to this recognition:

“…helping you see things within you so that you can do stuff. It’s like empowerment… Helping you see just how capable you are...”

Modelling self-compassion

It is common for patients to see care providers as having it all together, which at times can contribute to feelings of inferiority. Patients in our study said that when care providers thoughtfully shared minor instances of personal struggle or vulnerability, they felt less alone and had a model for practising self-compassion. Witnessing care providers’ humanity and their willingness to show themselves compassion made our patients feel inspired:

“Someone shared that they tripped up the stairs at the SkyTrain station…and they felt embarrassed…it was like, oh man, this is somebody that I viewed as all put together…something small and silly but it was just like… you see somebody trip up the stairs and you don’t think, oh my god what an idiot or those thoughts that you have when it happens to you.”

Another participant made an analogy between care providers practising self-compassion and walking down a fashion runway:

“They (care providers) use an example of self-compassion kind of similar to planting a seed—showing us what it could look like…and with the modelling you can…you’re not required to try on the clothing, you just watch everyone on the runway. You can see potential options, you don’t need to put it on yet.”

Self-compassion brings numerous health benefits and increases resilience through difficult life circumstances. Unfortunately, practising self-compassion is not easy for people with mental health conditions. Our work shows that validation is a powerful tool that helped individuals with eating disorders develop and practise self-compassion. Based on our research, we encourage people to use this tool by incorporating the following techniques:

be curious: make time to ask your loved one how they are doing and be open to explore their feelings with them

listen: when we listen actively, we create a deeper connection with our loved one and can identify what they need to feel supported

encourage: let your loved one know you recognize the hard work they are putting in towards their recovery

share: we shouldn’t be afraid to reveal our own struggles and imperfections; sharing lets people in recovery know they are not alone in tough times

Patients who participated in this study taught us that validation makes them feel seen, creates a sense of comfort, reduces conflict and gives them courage. These in turn helped them to overcome barriers to self-compassion. Our patients’ insights remind us that we all need validation and can all benefit from self-compassion. We hope these principles can guide loved ones and care providers in their relationships with individuals who are working on their mental health and recovery.

About the authors

Avarna is the research coordinator for the Provincial Adult Tertiary Specialized Eating Disorders Program at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver. Under the supervision of Dr. Geller, she is currently investigating the role self-compassion plays in recovery from an eating disorder

Dr. Geller is Director of Research at the Provincial Adult Tertiary Specialized Eating Disorders Program and an associate professor in the UBC Department of Psychiatry. Her program of research focuses on assessing and enhancing motivation for change, overcoming barriers to self-compassion and enhancing factors that contribute to collaborative, patient-centred care

Footnotes:

-

Gilbert, P. (Ed.). (2017). Compassion: Concepts, research and applications. Taylor & Francis.

-

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self‐compassion, self‐esteem, and well‐being. Social & Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 1–12.

-

Geller, J., Samson, L., Maiolino, N., Iyar, M. M., Kelly, A. C., & Srikameswaran, S. (2022). Self-compassion and its barriers: Predicting outcomes from inpatient and residential eating disorders treatment. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1), 1–10.

-

Lynch, T. R., Chapman, A. L., Rosenthal, M. Z., Kuo, J. R., & Linehan, M. M. (2006). Mechanisms of change in dialectical behavior therapy: Theoretical and empirical observations. Journal of clinical psychology, 62(4), 459–480.

-

Geller, J., Fernandes, A., Srikameswaran, S., Pullmer, R., & Marshall, S. (2021). The power of feeling seen: Perspectives on validation from individuals with eating disorders. Journal of Eating Disorders, 9, 149.