Reprinted from the "Systemic Racism" issue of Visions Journal, 2021, 16 (3), pp. 33-36

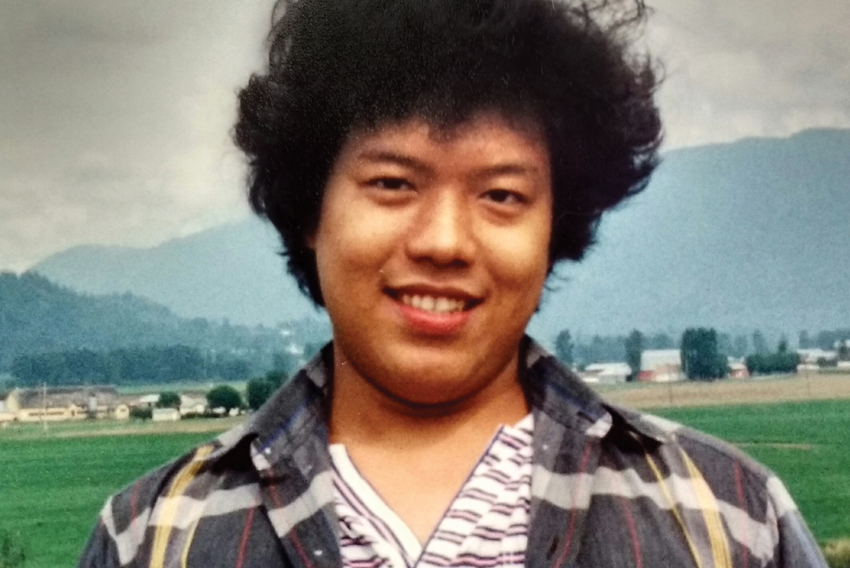

Kyaw Naing Din was born and grew up in Rangoon (Yangon), Burma (Myanmar). On August 14, 1990, at the age of 25, Kyaw immigrated to Canada with his father, Hla Din, mother, Hnin Myaing Din, three brothers, me, and another sister. We are a very close family, and we take care of one another. We came to Canada with the hope of starting a peaceful new life. Sadly, my father died in August 2014, and my mother died in February 2017.

Unfortunately, upon our arrival, Kyaw was mistreated by border guards at the airport. He was kept in a secluded area, made to wait, and interrogated with only me as his translator. He was accused of being an imposter, of fraudulently immigrating to Canada. None of their accusations had any merit, and eventually, they allowed Kyaw into Canada, but the experience was traumatizing for him and the rest of the family.

We initially lived in Abbotsford, BC, before we moved to Burnaby and then Coquitlam. Because Kyaw spoke and understood very little English, he attended English as a Second Language classes at the University of the Fraser Valley in Abbotsford. One day, while coming home from class, Kyaw was harassed by local police, who handcuffed him and drove him around for quite a while before letting him go, admitting they had falsely arrested him. This incident so discouraged Kyaw that he stopped attending ESL classes. His shock at his treatment by the Canadian authorities, and the trauma that resulted from those encounters, had severe effects on his mind and body.

Kyaw began to suffer from pains in his body. He told us that he heard voices once in a while, and heard voices talking to him specifically. Neither Kyaw nor his family members understood what was happening to him; he had never experienced these symptoms before.

Kyaw first saw a psychiatrist when he was in his early thirties. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia when he was about 35 years old and prescribed psychiatric medications, which can have very serious and dangerous side effects. Kyaw often experienced side effects from his medications, including tremors, slurred speech, involuntary movements, and facial twitches. He also became pre-diabetic. Kyaw was well as long as he was taking medication, but when he forgot to take it regularly and sometimes stopped taking it, he would experience mild mental confusion.

Kyaw was always appreciative of the people he dealt with in his life—like his physicians, his psychiatrist, his dentist, the nurses he saw at the hospitals and home, and the police officers and paramedics who transported him to the hospital.

As a poor immigrant, Kyaw both relied on public health care and experienced racism through it. Kyaw was not treated fairly because of his cultural and ethnic background. I would like to share how systemic racism blocked our beloved brother, Kyaw’s access to mental health care he needed from his psychiatrist. A few months before his death, Kyaw told his psychiatrist that he would like to change from a monthly injection to daily oral medication as he no longer wanted to take injections due to too much pain at the injection site. Both Kyaw and I greatly appreciated that she allowed the change. However, she denied my request that Kyaw take his medication at the pharmacy. The reason she gave was that it would be too expensive to have a pharmacy dispense medication daily.

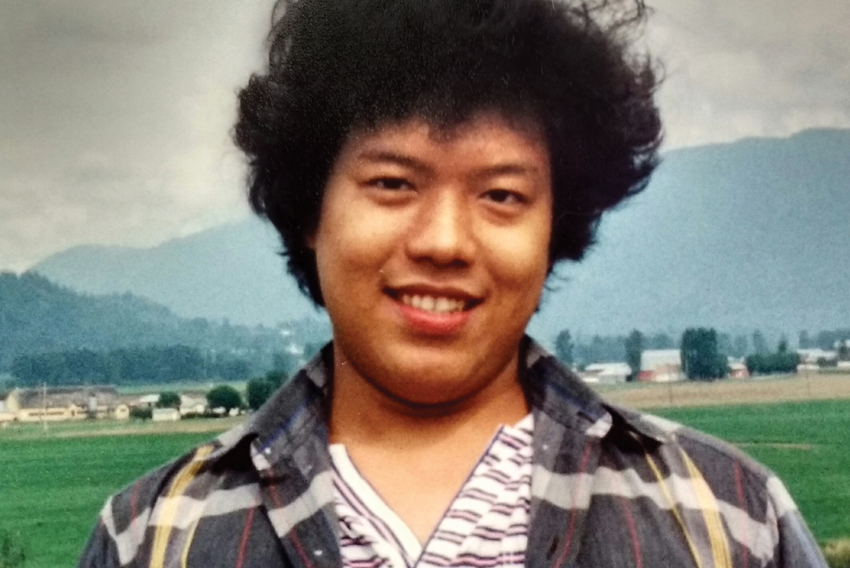

Kyaw Naing Din with his dog, on the left. Portrait of Kyaw Naing Din later in life, on the right.

My heart pounded and sank as I knew that without appropriate support, Kyaw would not take his medication regularly and, at some point, stop taking it and end up at the hospital again. We had always appreciated Kyaw’s psychiatrist for her care, but I felt that her decision was patronizing. I felt that, because of Kyaw’s ethnic background, he was not listened to or taken seriously.

Caring for Kyaw was not difficult because our family is close and we all loved him. He always brought joy and laughter to the people around him. When he suffered from mental confusion as a result of not taking his medication regularly, we would help him get to the hospital for a few days to get stabilized.

On August 11, 2019, I called the Ridge Meadows RCMP for help to take him to the hospital—he was suffering from mild mental confusion as he was not taking his medication. Kyaw did not have any problem going to the hospital with police assistance in the past.

I clearly explained to the dispatch in my initial 911 phone call that day, that although Kyaw said that he wanted to hit me, he had never hit me or anyone else and I and everyone at home were safe. I communicated that I was asking for police assistance to transport my brother to the hospital. I also explained that Kyaw was having some mild mental confusion as he had not taken medication for a few days. I explained that this kind of confusion had happened to him in the past, and he would become normal and well again within a few days once he gets to the hospital and back on his medication.

The two police officers who arrived saw that Kyaw’s situation was not urgent as he was peaceful—not violent, not shouting, not harming himself or anyone.

One of the police officers said that they would call an ambulance and told me to take my brother to the hospital by myself. An ambulance with two paramedics arrived quickly. I again went to Kyaw’s room where he was quietly and peacefully seated in the chair by his bed. I opened the door and told him that an ambulance had arrived and asked if he would like to go to the hospital. He replied that he did not like to go to the hospital at that time. I closed Kyaw’s bedroom door and explained to the paramedics and the police that Kyaw did not want to go.

I called my older sister, Hla Myaing Din, and two older brothers, Hla Shwe Din and Thant Zin Din, who were on the way. They suggested asking the police officers and the paramedics to leave for the time being and to call them when Kyaw was sleeping if necessary. I explained to the police officer that our older siblings were on the way and would arrive in five to ten minutes—that everything would be okay as Kyaw would listen to his older siblings and go to the hospital after they spoke to him. One of the police officers while talking on the cell phone (police radio) asked me the language Kyaw speaks. I told him that it was Burmese.

Within a few minutes, two additional police officers arrived. These additional officers insisted that they go and talk to Kyaw in his room. I told them that I was concerned that he might throw a bottle at them if he got upset. I openly requested the police officers not to shoot my brother. I told them that Kyaw is a good person, peaceful and not violent. One police officer said, “We don’t need to wait for your sister and brothers to arrive. We won’t shoot your brother. We know how to handle people like him who have mental health issues. We deal with them all the time.” The police officer said that he did not even have a gun, in a laughing voice.

Despite my repeated requests that they wait until Kyaw’s older siblings could arrive and help de-escalate the situation peacefully, the police entered Kyaw’s room and fatally shot him with a taser gun and a firearm in the face, head, and chest. They did not try to talk to him or warn him that they were entering his bedroom. The high-ranking police officer afterwards stated that he was informed Kyaw was suicidal, and that is why they did not wait for our siblings. But we were the ones to call 911, and we never said he was suicidal then, or when the police were at the house. I feel strongly that Kyaw was killed by the police for no justifiable reason. In the end, it was the helpers that we needed to be worried about, the ones who are supposed to serve and protect the public.

My siblings and I were kept outside of the house for hours after Kyaw was killed, with no news about whether he was alive or dead. As we cried in the front yard, I remember the paramedics and police laughing. To me, it seemed that they acted as if Kyaw’s life was unimportant.

Police officers are supposed to be trained in responding to people with mental health issues, without causing harm. However, the police officers did not de-escalate the situation. The police did not bring a mental health practitioner with them nor an interpreter. If the police officers had listened to my request not to enter Kyaw’s bedroom, Kyaw would be alive and well today.

My brother is gone, and the officers who were responsible for his death faced no consequences for their reckless actions. The Independent Investigations Office (the IIO, a civilian-led agency that conducts investigations when death or serious injury results from the actions of a police officer) refused to send the file to Crown Counsel for consideration of criminal charges against the police officers who caused my brother’s death. The IIO accepted the police officers’ versions of events at face value and did not believe the other witnesses’ accounts. They found that it was reasonable for police officers to refuse to wait for my siblings to arrive and talk to Kyaw, and found that there was no reason to suspect they could have been helpful. My family has been devastated by the IIO’s decision.

Kyaw was a kind, loving, and generous person. He had deep sympathy for marginalized and oppressed peoples. When he saw people asking for money on the streets, he always wanted to give them money. Our family always said that Kyaw was the best son and brother. Kyaw enjoyed and valued his everyday life. He used to spend time reading our mother’s Bible, drawing, listening to music, and watching movies. He loved his little dog and took care of her very well. He did a lot of daily chores for our family, such as washing dishes, cleaning the kitchen, doing the laundry, taking the garbage out, and so on. Kyaw was never tired of doing household chores for his aging parents when they were still with us.

My family and I are traumatized, shocked, and broken-hearted by Kyaw’s sudden and violent death. We cannot find words to express our agonizing pain and suffering for the irreplaceable loss of our beloved brother. I cannot describe in words the grief that smothers me whenever I think about Kyaw. I have wept countless times over his untimely and horrendous death. We still do not know the names of the police officers who killed our brother.

According to a 2018 report by the CBC, 461 people died through encounters with the police between 2000 and 2017.1 All of us, including people in the mental health care system, the criminal justice system, and the public, need to work together to stop police brutality and to get justice for all victims. The police officers who commit crimes and other forms of wrongdoing need to be held accountable for their actions. We, Kyaw’s grieving and traumatized family, hope that the public will help us to get a public inquiry into his death. Please help us to get justice for our beloved brother, Kyaw, who died so suddenly and unexpectedly in this horrendous way.

Related Resources

|

About the author

Yin Yin Hla Din is Kyaw’s sister. She is writing this article on behalf of Kyaw’s family members, who provided him with strong family support. Yin Yin accompanied Kyaw to every one of his medical appointments and acted as his next of kin and Power of Attorney

Footnotes:

-

Nicholson, K. & Maroux, J. (2018). Most Canadians killed in police encounters since 2000 had mental health or substance abuse issues. CBC News (April 4). cbc.ca/news/investigates/most-canadians-killed-in-police-encounters-since-2000-had-mental-health-or-substance-abuse-issues-1.4602916