"He is going crazy"

Reprinted from the COVID-19 issue of Visions Journal, 16 (2), pp. 19-23

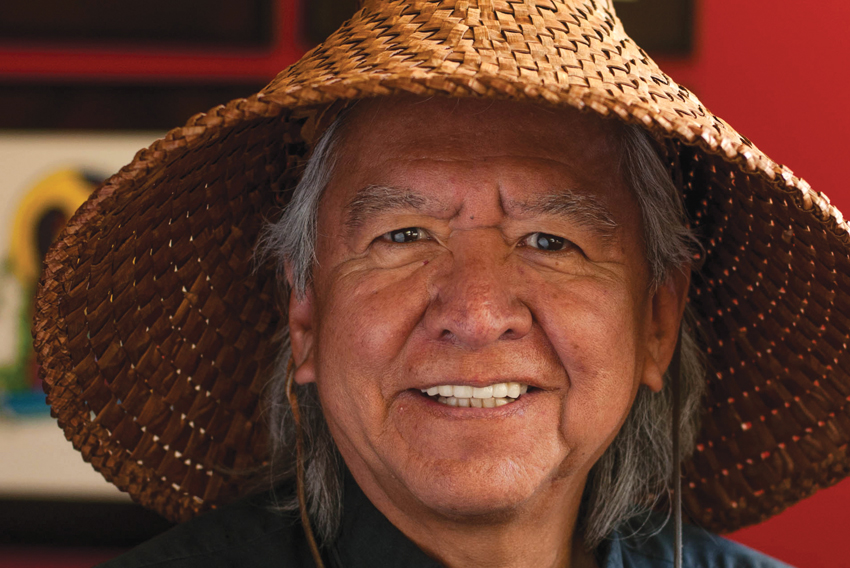

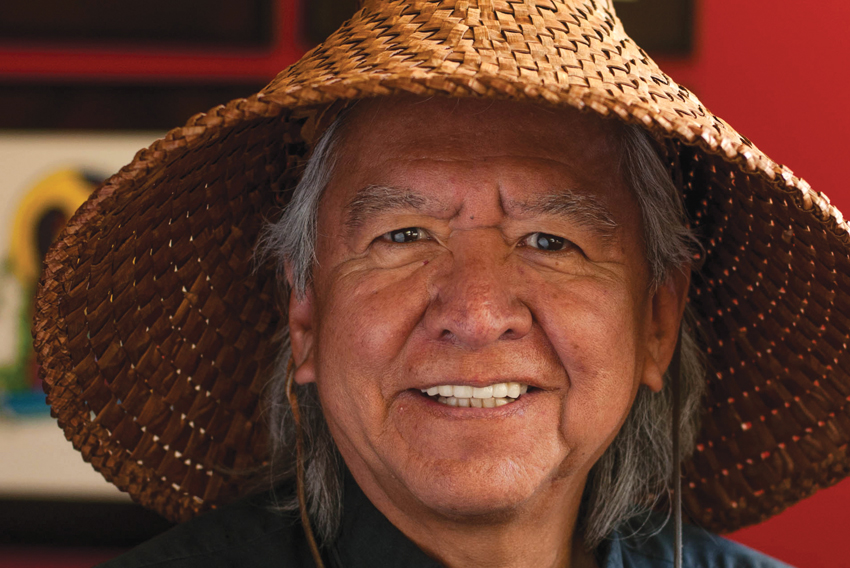

My story, I believe, is a reflection of what life is like for an Indigenous person growing up with the ongoing impacts of the colonization experience in Canada. My name is Saa Hiil Thut, aka Gerry Oldman. I am St'át'imc, from Shalalth, BC.

My goal is to create understanding of the importance of cultural relevance for human service workers and to inspire those who suffer from mental health and substance use issues. It is through understanding that we can take clear, direct action to achieve health and well-being. This has become even more important in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, when best health care practices encourage us to maintain physical distance from each other. The Indigenous peoples in this land have a long history of dealing with pandemics. Now more than ever it is important that we cultivate our ability to listen closely to each other. We must listen to those who remember our Indigenous history—particularly as we learn how to keep each other safe and as we learn new ways and relearn old ways of communicating with each other and sharing our experiences. Those who survived historical pandemics have much to teach us when it comes to preserving our mental health during the current pandemic and maintaining our vigilance in following the best health care practices.

The first understanding is that my people were sound in mind, body and spirit before contact with European colonizers. We did not have alcohol in our culture, so we did not have substance use issues. And we had effective ways to deal with mental health issues. Because of our philoso-phies and laws, and our diet and lifestyle, we lived healthy, long lives. My great-grandfather, for example, was 105 years old when he passed to the spirit world. The people at that time were taught that we were inter-connected with all of life and that we all needed each other. As a result, our way of life was sustainable. Nothing was in danger of extinction before colonization.

The Six Rs that have traumatized First Nations

The title of my article, "S-kee-ax," translates to "He is going crazy." I grew up hearing this word used to describe someone intoxicated by alcohol. I had heard Elders describe how, when the white people drank alcohol, they would start to laugh and stagger around and fall down and act crazy. So my ancestors were curious and first tried alcohol to satisfy their curiosity. But because they had never had alcohol before, the impact was felt quickly by individuals, families and communities. When the colonizers saw the extreme impacts that alcohol had on my people, they started to use it as a colonizing tool, and giving it away to my people in order to weaken us.

My people and I became the victims of a social-colonial process that had been used successfully in many other places all over the world. The colonizer's intention is to gain complete political and economic control over Indigenous territories. The colonizer knows how to use trauma to subjugate people. I have labeled this trauma-based plan of colonization "The Six Rs That Traumatized My People."

1. Racism

No human is born to be antagonistic or prejudiced against another human being. I have learned that all conflict is due to resources or ideology. In our case, it was both. We were not Christian, so we were “othered” by the colonizer as savage, pagan and heathen. Descriptions of us as "stupid," "crazy," "lazy," and "drunken" were also used by the colonizer to make us appear inferior to the Europeans who were coming to the new lands, instilling in the settlers the idea that the Indigenous were to be feared as they were devil-worshippers; this created the view that they were loathsome and disgusting. The territory that we occupied and used was rich in resources such as furs, gold, forests, water and farmable land. The colonizers’ appalling descriptions fuelled Indigenous-specific racism and opened the way for land theft, rape, murder and segregation in Canada.

2. Religion

I am constantly amazed and bewildered at how quickly the churches invaded all of our communities and dismantled the timeless ceremonies and rituals that had guided and bonded the clans. The trauma was imposed by the evil ministers, nuns and lay people who physically and sexually assaulted our children in our communities and the residential schools. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission reports that, in January 2015, there were nearly 38,000 registered claims for injuries resulting from physical and sexual abuse at Canadian residential schools.1

3. Reservations

Our Elders viewed the "Indian Reservations" to be nothing more than minimum security prisons. The reserves are situated on the least desirable plots of land; many did not have access to good water. After we were forced onto the reservations, the more desirable, resource-rich lands went to the settlers and immigrants. My people today, for the most part, live in poverty. Many in this system have become permanent wards of the state and are on welfare.

4. Residential schools

The residential school system was a breeding ground for dysfunction. It battered the children's sense of self-worth and fostered in them the belief that, as First Nations people, they didn't have the right to respect or fair and equal treatment. The residential school system was an evil genius in the dismantling of my people. A genius exerts a powerful influence—for good or evil, and in the instance of the residential school, it was evil indeed.

Physical and sexual abuse was part of every residential school in Canada. It was in the residential schools that we lost our identity as proud, vibrant Indigenous peoples. The mission of "taking the Indian out of the child" almost succeeded.2 The federal govern-ment and the churches have been found liable when it has been deter-mined that they knew of the ongoing abuse but did nothing to stop it.3

5. RCMP

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and other police forces were used to enforce the racist laws created to oppress and control the Indigenous peoples of this land. My people continue to mistrust and fear the police because we have lived experience of beatings, shootings and other violence at the hands of police force members.

It is often said that abuse and mistreatment are dehumanizing. This is true, but the description is often misattributed. Abuse and mistreatment do not dehumanize the victim. Abusers dehumanize themselves. In my opinion, which is rooted in my lived experience, when evil, individual members of the police force dehumanize themselves by abusing others, then both the individuals and the justice system are liable. The abuse continues because there is not an effective system in place to deal with officers who overstep the boundaries.

6. Removal

According to Canadian federal law, the First Nations peoples in Canada became wards of the state when the colonizers began occupying the land. During the Sixties Scoop, transfer payments were made to the provinces by the federal government for every Indigenous child apprehended and taken away from their Indigenous family and community—in other words, "scooped." These children were placed in foster care with non-Indigenous families or put up for adoption in non-Indigenous families. They ended up all over Canada, the US and Western Europe, losing all connection to their biological families and their Indigenous culture.

It is my belief, based on my personal and professional experience, that the 6 Rs have created what I call a trauma spectrum disorder. Someone with trauma spectrum disorder might be homeless, addicted, incarcerated, suicidal, or mentally and physically unhealthy, or they might be functional and self-supporting with mental and physical health issues, such as diabetes, addictions and a host of other preventable medical conditions.

Some exceptional individuals with trauma spectrum disorder have faced what caused them pain and suffering and have made healthy choices, worked on their personal healing and are successful in their chosen professions. But unfortunately, when someone struggles with trauma spectrum disorder, they often deal with daily triggers and suffering. Living this daily struggle creates extreme negative emotions.

In my personal and professional life, in discussions of poverty, addiction, suicide and child apprehension, I have heard individuals say, "Why can't they get over it?" or "What's wrong with those people?" But the appropriate question is, really, "What happened to you?" It is only when we really listen to the narratives of personal experience, when we understand the history of abuse of Indigenous peoples and individuals, that we can all take positive action towards healing.

Hi. My name is Gerry. I am a survivor of Kamloops Indian Residential School

I call myself a survivor of residential school because I am still alive. Many of my fellow students did not survive. But even though I survived residential school, my life became hateful to me; I had no desire to live or be successful. I did not even think success was possible. I had internalized the colonial message.

My first memories are of growing up as a child in a loving family. In my family, there was no tension from fear of negative emotions or consequences, no hunger. My first experience of this kind of fear, and of hunger, was in residential school. It was there that I first felt the anger in human hands and voice. In my first week at school, I knew the shame of making a mistake: I was slapped around my ears and face in front of the class. The combination—of the angry, arrogant voices of the teachers and the physical pain and punishment—destroyed my education experience.

Living in the dormitories of residential school, I also experienced and witnessed the fear of physical and sexual abuse at the hands of the dorm supervisors. I left the residential school as damaged goods.

I took up unhealthy activities to avoid the tension in my mind and body—tension that was a direct result of my lived experience in residential school. I used alcohol and drugs, and these acts of avoidance became addictive. As a trauma victim, I was angry, afraid and depressed. The actions I took to avoid these feelings led to my being unhealthy and dysfunctional at home and in the community.

My healing journey

I had been using alcohol and drugs for 14 years when I hit rock bottom. I was deeply depressed and had recurring thoughts of suicide. One morning, I woke up and I knew that the day had come to end my life.

My father had long ago gifted me a beautiful hunting rifle and told me I was to be the hunter for the family. I kept the hunting rifle under my bed. That morning, I got out of bed, took the hunting rifle and some shells, and started walking away from my family home, out of the community. I knew I could not kill myself within the circle of the community—I resolved to end my life outside. But as I walked past my younger brother's house, he saw me and called out and invited me into his house for coffee. I stepped through his front door and, without really knowing why, I handed him the rifle. "You are the hunter in the family, now," I said.

From that day on, I turned my life over to my culture. Thank goodness for the Elders and the Healers and Knowledge Keepers who taught me that when I faced my emotional pain, I could say goodbye to my problems. They guided me in ceremony intended to heal my mind, body and spirit. These ceremonies—the equivalent of no-talk therapy—had been used by my people successfully for generations to deal with a range of mental, physical and spiritual issues. The Elders tell us that, as humans, we act the way we think: if we think negative thoughts, we talk and act in negative ways. The ceremonies expanded my understanding of who I was; I started to choose more positive behaviours and started to shape strong, healthy relationships.

My medicine was in the Sweat Lodge and in the smudging ceremonies, the healing circles, the chanting circles, in meditation and fasting and in being a support to others. The ceremonies brought me to a place of being responsible for my words and actions. The Elders' message was to free myself from anger, fear and sadness. They taught me that these emotions didn't belong to me—and I didn't belong to them. I could let them go. I was told that my healing would be complete when I forgave my abusers. When I accepted this advice, I let go of my abusers and their abuse, and I was free.

I now understand that each day that I wake up, I can make a choice to be healthy and free, I can choose how I face the day and the challenges it might bring. We can heal ourselves as a people today because all of our prob-lems are man-made. Colonization is a product of humans, and we can heal ourselves from the negative impact of those events.

My healing journey combined Indig-enous ceremony and philosophy and culturally relevant counselling with a therapist who understood the impacts of trauma from the colonization process. My message to other victims and survivors is to find a way to free yourself. My advice to therapists, counsellors and agencies is to do everything you can do to acknowl-edge and honour in your practice therapies that are culturally and personally relevant to the individuals you work with.

In the context of COVID-19, that advice takes on new meaning. It requires creativity—on the part of victims, survivors and counsellors—to adapt culturally and personally relevant therapies to suit our new physically distant world. How do we share Indigenous culture over Zoom? How can we conduct a smudging ceremony? How can we meditate in front of a computer? How can we participate in a healing circle if we are sitting alone in our living room? It all sounds a bit hopeless. But it isn't. The philosophy behind Indigenous healing is that healing can be done at a distance. We must all take responsibility for making the abstract experience of digital interaction with each other more real, more human. It simply demands that we change our methods.

No hopeless cases

In 1975, I began working in an addictions program in my home community. But a year later, I did not have a single client. I told my chief that I was going to resign my position because I felt like a failure. He told me to give it another year and to change my methods.

I took his advice. I began to think about how I could change my practice to be more relevant to the people I was trying to help. I realized that one of the negative impacts of the colonial process was that many people had lost their connection to the land and to the skills that, for generations, had made our Indigenous communities vibrant, healthy, creative and self-sufficient. I started to take families out to harvest food on the land. It was at these camps that the people became active partici-pants in their own healing.

By changing my methods, I changed my relationships with my clients, and together we changed the nature of their healing experiences. From this I learned a valuable lesson: there are no hopeless cases, only hopeless methods.

Being able to adapt our methods is even more important during the COVID-19 pandemic. It's important to remember that Indigenous peoples have a history of abuse at the hands of so-called professionals, whether these were educators, medical care providers or legal authorities. As human service workers, we have to make an extra effort to connect with our clients, especially our Indigenous clients. We have an opportunity to promote new approaches to care, ones that encourage and acknowledge the benefit of self-isolation and introspection and the insights that come with sharing ceremonies and personal experiences in new ways. When we recognize the value of spending time alone, and explore sharing our thoughts and experiences in new ways—by Zoom, telephone and other digital communications technologies—then we can come to embrace growth and new understanding, in our relationships with each other and our relationship with self. I think of the Elders saying, "Free yourself from anger, from negative emotions." We all have that responsibility to free ourselves and support others to free themselves.

In closing, I would like to thank all of you who are answering the call to help people who are suffering from substance abuse and mental health issues. You are working in an honourable profession and the requirement is simply that you connect with people by being careful, creative and sincere in your work and always do your best.

About the author

Saa Hiil Thut (who is known by other names as well, such as Gerry Oleman and Gerry Oldman) is of St'át'imc descent and has been a human service worker since 1976, in addictions, abuse, family dynamics, cross-cultural education, cultural and spiritual support, traditional healing practices and guidance for mental health workers. Saa Hiil Thut hosts a podcast series called Teachings in the Air with Gerry Oldman. Gerry's website is www.gerryoleman.com

Footnotes:

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (p. 106). www.trc.ca/assets/pdf/Honouring_the_Truth_Reconciling_for_the_Future_July_23_2015.pdf.

- The line on which this phrase is based (and many different versions of it) has been attributed (and misattributed) to various historical figures. However, it is always used in the context of colonization, frequently violent cultural appropriation and assimilation; it aptly reflects the ideology of the colonizers in their imposition of the residential school system on the Indigenous peoples who live in what is now called North America.

- See, for example, Blackwater v. Plint, [2005] 3 S.C.R. 3, 2005 SCC 58.